This article is about evolution in biology. For related articles, see Outline of evolution. For other uses, see Evolution (disambiguation).

For a more accessible and less technical introduction to this topic, see Introduction to evolution.

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory

|

|

Fields and applications

|

All life on Earth shares a common ancestor known as the last universal ancestor,[3][4][5] which lived approximately 3.5–3.8 billion years ago,[6] although a study in 2015 found "remains of biotic life" from 4.1 billion years ago in ancient rocks in Western Australia.[7][8] According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth ... then it could be common in the universe."[7]

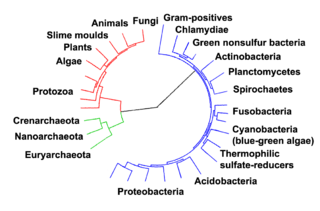

Repeated formation of new species (speciation), change within species (anagenesis), and loss of species (extinction) throughout the evolutionary history of life on Earth are demonstrated by shared sets of morphological and biochemical traits, including shared DNA sequences.[9] These shared traits are more similar among species that share a more recent common ancestor, and can be used to reconstruct a biological "tree of life" based on evolutionary relationships (phylogenetics), using both existing species and fossils. The fossil record includes a progression from early biogenic graphite,[10] to microbial mat fossils,[11][12][13] to fossilized multicellular organisms. Existing patterns of biodiversity have been shaped both by speciation and by extinction.[14] More than 99 percent of all species that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.[15][16] Estimates of Earth's current species range from 10 to 14 million,[17] of which about 1.2 million have been documented.[18]

In the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin formulated the scientific theory of evolution by natural selection, published in his book On the Origin of Species (1859). Evolution by natural selection is a process demonstrated by the observation that more offspring are produced than can possibly survive, along with three facts about populations: 1) traits vary among individuals with respect to morphology, physiology, and behaviour (phenotypic variation), 2) different traits confer different rates of survival and reproduction (differential fitness), and 3) traits can be passed from generation to generation (heritability of fitness).[19] Thus, in successive generations members of a population are replaced by progeny of parents better adapted to survive and reproduce in the biophysical environment in which natural selection takes place. This teleonomy is the quality whereby the process of natural selection creates and preserves traits that are seemingly fitted for the functional roles they perform.[20] Natural selection is the only known cause of adaptation but not the only known cause of evolution. Other, nonadaptive causes of microevolution include mutation and genetic drift.[21]

In the early 20th century the modern evolutionary synthesis integrated classical genetics with Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection through the discipline of population genetics. The importance of natural selection as a cause of evolution was accepted into other branches of biology. Moreover, previously held notions about evolution, such as orthogenesis, evolutionism, and other beliefs about innate "progress" within the largest-scale trends in evolution, became obsolete scientific theories.[22] Scientists continue to study various aspects of evolutionary biology by forming and testing hypotheses, constructing mathematical models of theoretical biology and biological theories, using observational data, and performing experiments in both the field and the laboratory.

Evolution is a cornerstone of modern science, accepted as one of the most reliably established of all facts and theories of science, based on evidence not just from the biological sciences but also from anthropology, psychology, astrophysics, chemistry, geology, physics, mathematics, and other scientific disciplines, as well as behavioral and social sciences. Understanding of evolution has made significant contributions to humanity, including the prevention and treatment of human disease, new agricultural products, industrial innovations, a subfield of computer science, and rapid advances in life sciences.[23][24][25] Discoveries in evolutionary biology have made a significant impact not just in the traditional branches of biology but also in other academic disciplines (e.g., biological anthropology and evolutionary psychology) and in society at large.[26][27]

Contents

History of evolutionary thought

Biologist and statistician Ronald Fisher

Main article: History of evolutionary thought

The proposal that one type of organism could descend from another type goes back to some of the first pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, such as Anaximander and Empedocles.[28] Such proposals survived into Roman times. The poet and philosopher Lucretius followed Empedocles in his masterwork De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things).[29][30] In contrast to these materialistic views, Aristotle understood all natural things, not only living things, as being imperfect actualisations of different fixed natural possibilities, known as "forms," "ideas," or (in Latin translations) "species."[31][32] This was part of his teleological understanding of nature in which all things have an intended role to play in a divine cosmic order. Variations of this idea became the standard understanding of the Middle Ages and were integrated into Christian

learning, but Aristotle did not demand that real types of organisms

always correspond one-for-one with exact metaphysical forms and

specifically gave examples of how new types of living things could come

to be.[33]In the 17th century, the new method of modern science rejected Aristotle's approach. It sought explanations of natural phenomena in terms of physical laws that were the same for all visible things and that did not require the existence of any fixed natural categories or divine cosmic order. However, this new approach was slow to take root in the biological sciences, the last bastion of the concept of fixed natural types. John Ray applied one of the previously more general terms for fixed natural types, "species," to plant and animal types, but he strictly identified each type of living thing as a species and proposed that each species could be defined by the features that perpetuated themselves generation after generation.[34] These species were designed by God, but showed differences caused by local conditions. The biological classification introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1735 explicitly recognized the hierarchical nature of species relationships, but still viewed species as fixed according to a divine plan.[35]

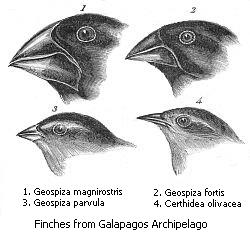

The crucial break from the concept of constant typological classes or types in biology came with the theory of evolution through natural selection, which was formulated by Charles Darwin in terms of variable populations. Partly influenced by An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798) by Thomas Robert Malthus, Darwin noted that population growth would lead to a "struggle for existence" in which favorable variations prevailed as others perished. In each generation, many offspring fail to survive to an age of reproduction because of limited resources. This could explain the diversity of plants and animals from a common ancestry through the working of natural laws in the same way for all types of organism.[48][49][50][51] Darwin developed his theory of "natural selection" from 1838 onwards and was writing up his "big book" on the subject when Alfred Russel Wallace sent him a version of virtually the same theory in 1858. Their separate papers were presented together at a 1858 meeting of the Linnean Society of London.[52] At the end of 1859, Darwin's publication of his "abstract" as On the Origin of Species explained natural selection in detail and in a way that led to an increasingly wide acceptance of concepts of evolution. Thomas Henry Huxley applied Darwin's ideas to humans, using paleontology and comparative anatomy to provide strong evidence that humans and apes shared a common ancestry. Some were disturbed by this since it implied that humans did not have a special place in the universe.[53]

Precise mechanisms of reproductive heritability and the origin of new traits remained a mystery. Towards this end, Darwin developed his provisional theory of pangenesis.[54] In 1865, Gregor Mendel reported that traits were inherited in a predictable manner through the independent assortment and segregation of elements (later known as genes). Mendel's laws of inheritance eventually supplanted most of Darwin's pangenesis theory.[55] August Weismann made the important distinction between germ cells that give rise to gametes (such as sperm and egg cells) and the somatic cells of the body, demonstrating that heredity passes through the germ line only. Hugo de Vries connected Darwin's pangenesis theory to Weismann's germ/soma cell distinction and proposed that Darwin's pangenes were concentrated in the cell nucleus and when expressed they could move into the cytoplasm to change the cells structure. De Vries was also one of the researchers who made Mendel's work well-known, believing that Mendelian traits corresponded to the transfer of heritable variations along the germline.[56] To explain how new variants originate, de Vries developed a mutation theory that led to a temporary rift between those who accepted Darwinian evolution and biometricians who allied with de Vries.[41][57][58] In the 1930s, pioneers in the field of population genetics, such as Ronald Fisher, Sewall Wright and J. B. S. Haldane set the foundations of evolution onto a robust statistical philosophy. The false contradiction between Darwin's theory, genetic mutations, and Mendelian inheritance was thus reconciled.[59]

In the 1920s and 1930s a modern evolutionary synthesis connected natural selection, mutation theory, and Mendelian inheritance into a unified theory that applied generally to any branch of biology. The modern synthesis was able to explain patterns observed across species in populations, through fossil transitions in palaeontology, and even complex cellular mechanisms in developmental biology.[41][60] The publication of the structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953 demonstrated a physical basis for inheritance.[61] Molecular biology improved our understanding of the relationship between genotype and phenotype. Advancements were also made in phylogenetic systematics, mapping the transition of traits into a comparative and testable framework through the publication and use of evolutionary trees.[62][63] In 1973, evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky penned that "nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution," because it has brought to light the relations of what first seemed disjointed facts in natural history into a coherent explanatory body of knowledge that describes and predicts many observable facts about life on this planet.[64]

Since then, the modern synthesis has been further extended to explain biological phenomena across the full and integrative scale of the biological hierarchy, from genes to species. This extension, known as evolutionary developmental biology and informally called "evo-devo," emphasises how changes between generations (evolution) acts on patterns of change within individual organisms (development).[65][66][67]

Heredity

The complete set of observable traits that make up the structure and behaviour of an organism is called its phenotype. These traits come from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.[70] As a result, many aspects of an organism's phenotype are not inherited. For example, suntanned skin comes from the interaction between a person's genotype and sunlight; thus, suntans are not passed on to people's children. However, some people tan more easily than others, due to differences in genotypic variation; a striking example are people with the inherited trait of albinism, who do not tan at all and are very sensitive to sunburn.[71]

Heritable traits are passed from one generation to the next via DNA, a molecule that encodes genetic information.[69] DNA is a long biopolymer composed of four types of bases. The sequence of bases along a particular DNA molecule specify the genetic information, in a manner similar to a sequence of letters spelling out a sentence. Before a cell divides, the DNA is copied, so that each of the resulting two cells will inherit the DNA sequence. Portions of a DNA molecule that specify a single functional unit are called genes; different genes have different sequences of bases. Within cells, the long strands of DNA form condensed structures called chromosomes. The specific location of a DNA sequence within a chromosome is known as a locus. If the DNA sequence at a locus varies between individuals, the different forms of this sequence are called alleles. DNA sequences can change through mutations, producing new alleles. If a mutation occurs within a gene, the new allele may affect the trait that the gene controls, altering the phenotype of the organism.[72] However, while this simple correspondence between an allele and a trait works in some cases, most traits are more complex and are controlled by quantitative trait loci (multiple interacting genes).[73][74]

Recent findings have confirmed important examples of heritable changes that cannot be explained by changes to the sequence of nucleotides in the DNA. These phenomena are classed as epigenetic inheritance systems.[75] DNA methylation marking chromatin, self-sustaining metabolic loops, gene silencing by RNA interference and the three-dimensional conformation of proteins (such as prions) are areas where epigenetic inheritance systems have been discovered at the organismic level.[76][77] Developmental biologists suggest that complex interactions in genetic networks and communication among cells can lead to heritable variations that may underlay some of the mechanics in developmental plasticity and canalisation.[78] Heritability may also occur at even larger scales. For example, ecological inheritance through the process of niche construction is defined by the regular and repeated activities of organisms in their environment. This generates a legacy of effects that modify and feed back into the selection regime of subsequent generations. Descendants inherit genes plus environmental characteristics generated by the ecological actions of ancestors.[79] Other examples of heritability in evolution that are not under the direct control of genes include the inheritance of cultural traits and symbiogenesis.[80][81]

Variation

White peppered moth

Black morph in peppered moth evolution

Further information: Genetic diversity and Population genetics

An individual organism's phenotype results from both its genotype and

the influence from the environment it has lived in. A substantial part

of the phenotypic variation in a population is caused by genotypic

variation.[74]

The modern evolutionary synthesis defines evolution as the change over

time in this genetic variation. The frequency of one particular allele

will become more or less prevalent relative to other forms of that gene.

Variation disappears when a new allele reaches the point of fixation—when it either disappears from the population or replaces the ancestral allele entirely.[82]Natural selection will only cause evolution if there is enough genetic variation in a population. Before the discovery of Mendelian genetics, one common hypothesis was blending inheritance. But with blending inheritance, genetic variance would be rapidly lost, making evolution by natural selection implausible. The Hardy–Weinberg principle provides the solution to how variation is maintained in a population with Mendelian inheritance. The frequencies of alleles (variations in a gene) will remain constant in the absence of selection, mutation, migration and genetic drift.[83]

Variation comes from mutations in the genome, reshuffling of genes through sexual reproduction and migration between populations (gene flow). Despite the constant introduction of new variation through mutation and gene flow, most of the genome of a species is identical in all individuals of that species.[84] However, even relatively small differences in genotype can lead to dramatic differences in phenotype: for example, chimpanzees and humans differ in only about 5% of their genomes.[85]

Mutation

Main article: Mutation

Duplication of part of a chromosome

Mutations can involve large sections of a chromosome becoming duplicated (usually by genetic recombination), which can introduce extra copies of a gene into a genome.[87] Extra copies of genes are a major source of the raw material needed for new genes to evolve.[88] This is important because most new genes evolve within gene families from pre-existing genes that share common ancestors.[89] For example, the human eye uses four genes to make structures that sense light: three for colour vision and one for night vision; all four are descended from a single ancestral gene.[90]

New genes can be generated from an ancestral gene when a duplicate copy mutates and acquires a new function. This process is easier once a gene has been duplicated because it increases the redundancy of the system; one gene in the pair can acquire a new function while the other copy continues to perform its original function.[91][92] Other types of mutations can even generate entirely new genes from previously noncoding DNA.[93][94]

The generation of new genes can also involve small parts of several genes being duplicated, with these fragments then recombining to form new combinations with new functions.[95][96] When new genes are assembled from shuffling pre-existing parts, domains act as modules with simple independent functions, which can be mixed together to produce new combinations with new and complex functions.[97] For example, polyketide synthases are large enzymes that make antibiotics; they contain up to one hundred independent domains that each catalyse one step in the overall process, like a step in an assembly line.[98]

Sex and recombination

Further information: Sexual reproduction, Genetic recombination and Evolution of sexual reproduction

In asexual organisms, genes are inherited together, or linked, as they cannot mix with genes of other organisms during reproduction. In contrast, the offspring of sexual

organisms contain random mixtures of their parents' chromosomes that

are produced through independent assortment. In a related process called

homologous recombination, sexual organisms exchange DNA between two matching chromosomes.[99]

Recombination and reassortment do not alter allele frequencies, but

instead change which alleles are associated with each other, producing

offspring with new combinations of alleles.[100] Sex usually increases genetic variation and may increase the rate of evolution.[101][102]Gene flow

Further information: Gene flow

Gene flow is the exchange of genes between populations and between species.[108]

It can therefore be a source of variation that is new to a population

or to a species. Gene flow can be caused by the movement of individuals

between separate populations of organisms, as might be caused by the

movement of mice between inland and coastal populations, or the movement

of pollen between heavy metal tolerant and heavy metal sensitive populations of grasses.Gene transfer between species includes the formation of hybrid organisms and horizontal gene transfer. Horizontal gene transfer is the transfer of genetic material from one organism to another organism that is not its offspring; this is most common among bacteria.[109] In medicine, this contributes to the spread of antibiotic resistance, as when one bacteria acquires resistance genes it can rapidly transfer them to other species.[110] Horizontal transfer of genes from bacteria to eukaryotes such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the adzuki bean weevil Callosobruchus chinensis has occurred.[111][112] An example of larger-scale transfers are the eukaryotic bdelloid rotifers, which have received a range of genes from bacteria, fungi and plants.[113] Viruses can also carry DNA between organisms, allowing transfer of genes even across biological domains.[114]

Large-scale gene transfer has also occurred between the ancestors of eukaryotic cells and bacteria, during the acquisition of chloroplasts and mitochondria. It is possible that eukaryotes themselves originated from horizontal gene transfers between bacteria and archaea.[115]

Mechanisms

Mutation followed by natural selection, results in a population with darker colouration.

Natural selection

Further information: Natural selection and Fitness (biology)

Evolution by means of natural selection is the process by which

traits that enhance survival and reproduction become more common in

successive generations of a population. It has often been called a

"self-evident" mechanism because it necessarily follows from three

simple facts:[19]- Variation exists within populations of organisms with respect to morphology, physiology, and behaviour (phenotypic variation).

- Different traits confer different rates of survival and reproduction (differential fitness).

- These traits can be passed from generation to generation (heritability of fitness).

The central concept of natural selection is the evolutionary fitness of an organism.[117] Fitness is measured by an organism's ability to survive and reproduce, which determines the size of its genetic contribution to the next generation.[117] However, fitness is not the same as the total number of offspring: instead fitness is indicated by the proportion of subsequent generations that carry an organism's genes.[118] For example, if an organism could survive well and reproduce rapidly, but its offspring were all too small and weak to survive, this organism would make little genetic contribution to future generations and would thus have low fitness.[117]

If an allele increases fitness more than the other alleles of that gene, then with each generation this allele will become more common within the population. These traits are said to be "selected for." Examples of traits that can increase fitness are enhanced survival and increased fecundity. Conversely, the lower fitness caused by having a less beneficial or deleterious allele results in this allele becoming rarer—they are "selected against."[119] Importantly, the fitness of an allele is not a fixed characteristic; if the environment changes, previously neutral or harmful traits may become beneficial and previously beneficial traits become harmful.[72] However, even if the direction of selection does reverse in this way, traits that were lost in the past may not re-evolve in an identical form (see Dollo's law).[120][121]

A chart showing three types of selection.

1. Disruptive selection

2. Stabilising selection

3. Directional selection

1. Disruptive selection

2. Stabilising selection

3. Directional selection

A special case of natural selection is sexual selection, which is selection for any trait that increases mating success by increasing the attractiveness of an organism to potential mates.[124] Traits that evolved through sexual selection are particularly prominent among males of several animal species. Although sexually favoured, traits such as cumbersome antlers, mating calls, large body size and bright colours often attract predation, which compromises the survival of individual males.[125][126] This survival disadvantage is balanced by higher reproductive success in males that show these hard-to-fake, sexually selected traits.[127]

Natural selection most generally makes nature the measure against which individuals and individual traits, are more or less likely to survive. "Nature" in this sense refers to an ecosystem, that is, a system in which organisms interact with every other element, physical as well as biological, in their local environment. Eugene Odum, a founder of ecology, defined an ecosystem as: "Any unit that includes all of the organisms...in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity and material cycles (ie: exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system."[128] Each population within an ecosystem occupies a distinct niche, or position, with distinct relationships to other parts of the system. These relationships involve the life history of the organism, its position in the food chain and its geographic range. This broad understanding of nature enables scientists to delineate specific forces which, together, comprise natural selection.

Natural selection can act at different levels of organisation, such as genes, cells, individual organisms, groups of organisms and species.[129][130][131] Selection can act at multiple levels simultaneously.[132] An example of selection occurring below the level of the individual organism are genes called transposons, which can replicate and spread throughout a genome.[133] Selection at a level above the individual, such as group selection, may allow the evolution of cooperation, as discussed below.[134]

Biased mutation

In addition to being a major source of variation, mutation may also function as a mechanism of evolution when there are different probabilities at the molecular level for different mutations to occur, a process known as mutation bias.[135] If two genotypes, for example one with the nucleotide G and another with the nucleotide A in the same position, have the same fitness, but mutation from G to A happens more often than mutation from A to G, then genotypes with A will tend to evolve.[136] Different insertion vs. deletion mutation biases in different taxa can lead to the evolution of different genome sizes.[137][138] Developmental or mutational biases have also been observed in morphological evolution.[139][140] For example, according to the phenotype-first theory of evolution, mutations can eventually cause the genetic assimilation of traits that were previously induced by the environment.[141][142]Mutation bias effects are superimposed on other processes. If selection would favor either one out of two mutations, but there is no extra advantage to having both, then the mutation that occurs the most frequently is the one that is most likely to become fixed in a population.[143][144] Mutations leading to the loss of function of a gene are much more common than mutations that produce a new, fully functional gene. Most loss of function mutations are selected against. But when selection is weak, mutation bias towards loss of function can affect evolution.[145] For example, pigments are no longer useful when animals live in the darkness of caves, and tend to be lost.[146] This kind of loss of function can occur because of mutation bias, and/or because the function had a cost, and once the benefit of the function disappeared, natural selection leads to the loss. Loss of sporulation ability in Bacillus subtilis during laboratory evolution appears to have been caused by mutation bias, rather than natural selection against the cost of maintaining sporulation ability.[147] When there is no selection for loss of function, the speed at which loss evolves depends more on the mutation rate than it does on the effective population size,[148] indicating that it is driven more by mutation bias than by genetic drift. In parasatic organisms, mutation bias leads to selection pressures as seen in Ehrlichia. Mutations are biased towards antigenic variants in outer-membrane proteins.

Genetic drift

Further information: Genetic drift and Effective population size

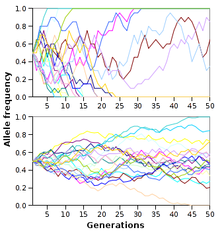

Simulation of genetic drift of 20 unlinked alleles in populations of 10 (top) and 100 (bottom). Drift to fixation is more rapid in the smaller population.

It is usually difficult to measure the relative importance of selection and neutral processes, including drift.[151] The comparative importance of adaptive and non-adaptive forces in driving evolutionary change is an area of current research.[152]

The neutral theory of molecular evolution proposed that most evolutionary changes are the result of the fixation of neutral mutations by genetic drift.[21] Hence, in this model, most genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift.[153] This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned, since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature.[154][155] However, a more recent and better-supported version of this model is the nearly neutral theory, where a mutation that would be effectively neutral in a small population is not necessarily neutral in a large population.[116] Other alternative theories propose that genetic drift is dwarfed by other stochastic forces in evolution, such as genetic hitchhiking, also known as genetic draft.[149][156][157]

The time for a neutral allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on population size, with fixation occurring more rapidly in smaller populations.[158] The number of individuals in a population is not critical, but instead a measure known as the effective population size.[159] The effective population is usually smaller than the total population since it takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding and the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest.[159] The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.[160]

Genetic hitchhiking

Recombination allows alleles on the same strand of DNA to become separated. However, the rate of recombination is low (approximately two events per chromosome per generation). As a result, genes close together on a chromosome may not always be shuffled away from each other and genes that are close together tend to be inherited together, a phenomenon known as linkage.[161] This tendency is measured by finding how often two alleles occur together on a single chromosome compared to expectations, which is called their linkage disequilibrium. A set of alleles that is usually inherited in a group is called a haplotype. This can be important when one allele in a particular haplotype is strongly beneficial: natural selection can drive a selective sweep that will also cause the other alleles in the haplotype to become more common in the population; this effect is called genetic hitchhiking or genetic draft.[162] Genetic draft caused by the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that are under selection can be partially captured by an appropriate effective population size.[156]Gene flow

Gene flow involves the exchange of genes between populations and between species.[108] The presence or absence of gene flow fundamentally changes the course of evolution. Due to the complexity of organisms, any two completely isolated populations will eventually evolve genetic incompatibilities through neutral processes, as in the Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller model, even if both populations remain essentially identical in terms of their adaptation to the environment.If genetic differentiation between populations develops, gene flow between populations can introduce traits or alleles which are disadvantageous in the local population and this may lead to organisms within these populations evolving mechanisms that prevent mating with genetically distant populations, eventually resulting in the appearance of new species. Thus, exchange of genetic information between individuals is fundamentally important for the development of the biological species concept.

During the development of the modern synthesis, Sewall Wright developed his shifting balance theory, which regarded gene flow between partially isolated populations as an important aspect of adaptive evolution.[163] However, recently there has been substantial criticism of the importance of the shifting balance theory.[164]

Outcomes

Evolution influences every aspect of the form and behaviour of organisms. Most prominent are the specific behavioural and physical adaptations that are the outcome of natural selection. These adaptations increase fitness by aiding activities such as finding food, avoiding predators or attracting mates. Organisms can also respond to selection by cooperating with each other, usually by aiding their relatives or engaging in mutually beneficial symbiosis. In the longer term, evolution produces new species through splitting ancestral populations of organisms into new groups that cannot or will not interbreed.These outcomes of evolution are distinguished based on time scale as macroevolution versus microevolution. Macroevolution refers to evolution that occurs at or above the level of species, in particular speciation and extinction; whereas microevolution refers to smaller evolutionary changes within a species or population, in particular shifts in gene frequency and adaptation.[165] In general, macroevolution is regarded as the outcome of long periods of microevolution.[166] Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one—the difference is simply the time involved.[167] However, in macroevolution, the traits of the entire species may be important. For instance, a large amount of variation among individuals allows a species to rapidly adapt to new habitats, lessening the chance of it going extinct, while a wide geographic range increases the chance of speciation, by making it more likely that part of the population will become isolated. In this sense, microevolution and macroevolution might involve selection at different levels—with microevolution acting on genes and organisms, versus macroevolutionary processes such as species selection acting on entire species and affecting their rates of speciation and extinction.[168][169][170]

A common misconception is that evolution has goals, long-term plans, or an innate tendency for "progress," as expressed in beliefs such as orthogenesis and evolutionism; realistically however, evolution has no long-term goal and does not necessarily produce greater complexity.[171][172][173] Although complex species have evolved, they occur as a side effect of the overall number of organisms increasing and simple forms of life still remain more common in the biosphere.[174] For example, the overwhelming majority of species are microscopic prokaryotes, which form about half the world's biomass despite their small size,[175] and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity.[176] Simple organisms have therefore been the dominant form of life on Earth throughout its history and continue to be the main form of life up to the present day, with complex life only appearing more diverse because it is more noticeable.[177] Indeed, the evolution of microorganisms is particularly important to modern evolutionary research, since their rapid reproduction allows the study of experimental evolution and the observation of evolution and adaptation in real time.[178][179]

Adaptation

For more details on this topic, see Adaptation.

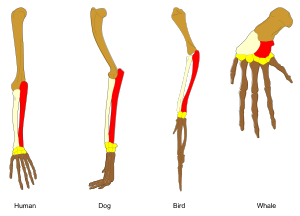

Homologous bones in the limbs of tetrapods. The bones of these animals have the same basic structure, but have been adapted for specific uses.

- Adaptation is the evolutionary process whereby an organism becomes better able to live in its habitat or habitats.[183]

- Adaptedness is the state of being adapted: the degree to which an organism is able to live and reproduce in a given set of habitats.[184]

- An adaptive trait is an aspect of the developmental pattern of the organism which enables or enhances the probability of that organism surviving and reproducing.[185]

A baleen whale skeleton, a and b label flipper bones, which were adapted from front leg bones: while c indicates vestigial leg bones, suggesting an adaptation from land to sea.[197]

During evolution, some structures may lose their original function and become vestigial structures.[202] Such structures may have little or no function in a current species, yet have a clear function in ancestral species, or other closely related species. Examples include pseudogenes,[203] the non-functional remains of eyes in blind cave-dwelling fish,[204] wings in flightless birds,[205] the presence of hip bones in whales and snakes,[197] and sexual traits in organisms that reproduce via asexual reproduction.[206] Examples of vestigial structures in humans include wisdom teeth,[207] the coccyx,[202] the vermiform appendix,[202] and other behavioural vestiges such as goose bumps[208][209] and primitive reflexes.[210][211][212]

However, many traits that appear to be simple adaptations are in fact exaptations: structures originally adapted for one function, but which coincidentally became somewhat useful for some other function in the process.[213] One example is the African lizard Holaspis guentheri, which developed an extremely flat head for hiding in crevices, as can be seen by looking at its near relatives. However, in this species, the head has become so flattened that it assists in gliding from tree to tree—an exaptation.[213] Within cells, molecular machines such as the bacterial flagella[214] and protein sorting machinery[215] evolved by the recruitment of several pre-existing proteins that previously had different functions.[165] Another example is the recruitment of enzymes from glycolysis and xenobiotic metabolism to serve as structural proteins called crystallins within the lenses of organisms' eyes.[216][217]

An area of current investigation in evolutionary developmental biology is the developmental basis of adaptations and exaptations.[218] This research addresses the origin and evolution of embryonic development and how modifications of development and developmental processes produce novel features.[219] These studies have shown that evolution can alter development to produce new structures, such as embryonic bone structures that develop into the jaw in other animals instead forming part of the middle ear in mammals.[220] It is also possible for structures that have been lost in evolution to reappear due to changes in developmental genes, such as a mutation in chickens causing embryos to grow teeth similar to those of crocodiles.[221] It is now becoming clear that most alterations in the form of organisms are due to changes in a small set of conserved genes.[222]

Coevolution

Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) which has evolved resistance to tetrodotoxin in its amphibian prey.

Further information: Coevolution

Interactions between organisms can produce both conflict and

cooperation. When the interaction is between pairs of species, such as a

pathogen and a host,

or a predator and its prey, these species can develop matched sets of

adaptations. Here, the evolution of one species causes adaptations in a

second species. These changes in the second species then, in turn, cause

new adaptations in the first species. This cycle of selection and

response is called coevolution.[223] An example is the production of tetrodotoxin in the rough-skinned newt and the evolution of tetrodotoxin resistance in its predator, the common garter snake. In this predator-prey pair, an evolutionary arms race has produced high levels of toxin in the newt and correspondingly high levels of toxin resistance in the snake.[224]Cooperation

Further information: Co-operation (evolution)

Not all co-evolved interactions between species involve conflict.[225]

Many cases of mutually beneficial interactions have evolved. For

instance, an extreme cooperation exists between plants and the mycorrhizal fungi that grow on their roots and aid the plant in absorbing nutrients from the soil.[226] This is a reciprocal relationship as the plants provide the fungi with sugars from photosynthesis. Here, the fungi actually grow inside plant cells, allowing them to exchange nutrients with their hosts, while sending signals that suppress the plant immune system.[227]Coalitions between organisms of the same species have also evolved. An extreme case is the eusociality found in social insects, such as bees, termites and ants, where sterile insects feed and guard the small number of organisms in a colony that are able to reproduce. On an even smaller scale, the somatic cells that make up the body of an animal limit their reproduction so they can maintain a stable organism, which then supports a small number of the animal's germ cells to produce offspring. Here, somatic cells respond to specific signals that instruct them whether to grow, remain as they are, or die. If cells ignore these signals and multiply inappropriately, their uncontrolled growth causes cancer.[228]

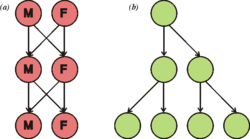

Such cooperation within species may have evolved through the process of kin selection, which is where one organism acts to help raise a relative's offspring.[229] This activity is selected for because if the helping individual contains alleles which promote the helping activity, it is likely that its kin will also contain these alleles and thus those alleles will be passed on.[230] Other processes that may promote cooperation include group selection, where cooperation provides benefits to a group of organisms.[231]

Speciation

Further information: Speciation

The four mechanisms of speciation

There are multiple ways to define the concept of "species." The choice of definition is dependent on the particularities of the species concerned.[233] For example, some species concepts apply more readily toward sexually reproducing organisms while others lend themselves better toward asexual organisms. Despite the diversity of various species concepts, these various concepts can be placed into one of three broad philosophical approaches: interbreeding, ecological and phylogenetic.[234] The Biological Species Concept (BSC) is a classic example of the interbreeding approach. Defined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, the BSC states that "species are groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[235] Despite its wide and long-term use, the BSC like others is not without controversy, for example because these concepts cannot be applied to prokaryotes,[236] and this is called the species problem.[233] Some researchers have attempted a unifying monistic definition of species, while others adopt a pluralistic approach and suggest that there may be different ways to logically interpret the definition of a species.[233][234]

Barriers to reproduction between two diverging sexual populations are required for the populations to become new species. Gene flow may slow this process by spreading the new genetic variants also to the other populations. Depending on how far two species have diverged since their most recent common ancestor, it may still be possible for them to produce offspring, as with horses and donkeys mating to produce mules.[237] Such hybrids are generally infertile. In this case, closely related species may regularly interbreed, but hybrids will be selected against and the species will remain distinct. However, viable hybrids are occasionally formed and these new species can either have properties intermediate between their parent species, or possess a totally new phenotype.[238] The importance of hybridisation in producing new species of animals is unclear, although cases have been seen in many types of animals,[239] with the gray tree frog being a particularly well-studied example.[240]

Speciation has been observed multiple times under both controlled laboratory conditions and in nature.[241] In sexually reproducing organisms, speciation results from reproductive isolation followed by genealogical divergence. There are four mechanisms for speciation. The most common in animals is allopatric speciation, which occurs in populations initially isolated geographically, such as by habitat fragmentation or migration. Selection under these conditions can produce very rapid changes in the appearance and behaviour of organisms.[242][243] As selection and drift act independently on populations isolated from the rest of their species, separation may eventually produce organisms that cannot interbreed.[244]

The second mechanism of speciation is peripatric speciation, which occurs when small populations of organisms become isolated in a new environment. This differs from allopatric speciation in that the isolated populations are numerically much smaller than the parental population. Here, the founder effect causes rapid speciation after an increase in inbreeding increases selection on homozygotes, leading to rapid genetic change.[245]

The third mechanism of speciation is parapatric speciation. This is similar to peripatric speciation in that a small population enters a new habitat, but differs in that there is no physical separation between these two populations. Instead, speciation results from the evolution of mechanisms that reduce gene flow between the two populations.[232] Generally this occurs when there has been a drastic change in the environment within the parental species' habitat. One example is the grass Anthoxanthum odoratum, which can undergo parapatric speciation in response to localised metal pollution from mines.[246] Here, plants evolve that have resistance to high levels of metals in the soil. Selection against interbreeding with the metal-sensitive parental population produced a gradual change in the flowering time of the metal-resistant plants, which eventually produced complete reproductive isolation. Selection against hybrids between the two populations may cause reinforcement, which is the evolution of traits that promote mating within a species, as well as character displacement, which is when two species become more distinct in appearance.[247]

Finally, in sympatric speciation species diverge without geographic isolation or changes in habitat. This form is rare since even a small amount of gene flow may remove genetic differences between parts of a population.[248] Generally, sympatric speciation in animals requires the evolution of both genetic differences and non-random mating, to allow reproductive isolation to evolve.[249]

One type of sympatric speciation involves crossbreeding of two related species to produce a new hybrid species. This is not common in animals as animal hybrids are usually sterile. This is because during meiosis the homologous chromosomes from each parent are from different species and cannot successfully pair. However, it is more common in plants because plants often double their number of chromosomes, to form polyploids.[250] This allows the chromosomes from each parental species to form matching pairs during meiosis, since each parent's chromosomes are represented by a pair already.[251] An example of such a speciation event is when the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana and Arabidopsis arenosa crossbred to give the new species Arabidopsis suecica.[252] This happened about 20,000 years ago,[253] and the speciation process has been repeated in the laboratory, which allows the study of the genetic mechanisms involved in this process.[254] Indeed, chromosome doubling within a species may be a common cause of reproductive isolation, as half the doubled chromosomes will be unmatched when breeding with undoubled organisms.[255]

Speciation events are important in the theory of punctuated equilibrium, which accounts for the pattern in the fossil record of short "bursts" of evolution interspersed with relatively long periods of stasis, where species remain relatively unchanged.[256] In this theory, speciation and rapid evolution are linked, with natural selection and genetic drift acting most strongly on organisms undergoing speciation in novel habitats or small populations. As a result, the periods of stasis in the fossil record correspond to the parental population and the organisms undergoing speciation and rapid evolution are found in small populations or geographically restricted habitats and therefore rarely being preserved as fossils.[169]

Extinction

Further information: Extinction

Tyrannosaurus rex. Non-avian dinosaurs died out in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period.

The role of extinction in evolution is not very well understood and may depend on which type of extinction is considered.[260] The causes of the continuous "low-level" extinction events, which form the majority of extinctions, may be the result of competition between species for limited resources (the competitive exclusion principle).[65] If one species can out-compete another, this could produce species selection, with the fitter species surviving and the other species being driven to extinction.[130] The intermittent mass extinctions are also important, but instead of acting as a selective force, they drastically reduce diversity in a nonspecific manner and promote bursts of rapid evolution and speciation in survivors.[264]

Evolutionary history of life

-4500 —

–

-4000 —

–

-3500 —

–

-3000 —

–

-2500 —

–

-2000 —

–

-1500 —

–

-1000 —

–

-500 —

–

0 —

Axis scale: Millions of years ago.

Main article: Evolutionary history of life

Origin of life

The Earth is about 4.54 billion years old.[265][266][267] The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago,[6][268] during the Eoarchean Era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean Eon. Microbial mat fossils have been found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone in Western Australia.[11][12][13] Other early physical evidence of a biogenic substance is graphite in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks discovered in Western Greenland[10] as well as "remains of biotic life" found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.[7][8] According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth … then it could be common in the universe."[7]More than 99 percent of all species, amounting to over five billion species,[269] that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.[15][16] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[17] of which about 1.2 million have been documented and over 86 percent have not yet been described.[18]

Highly energetic chemistry is thought to have produced a self-replicating molecule around 4 billion years ago, and half a billion years later the last common ancestor of all life existed.[4] The current scientific consensus is that the complex biochemistry that makes up life came from simpler chemical reactions.[270] The beginning of life may have included self-replicating molecules such as RNA[271] and the assembly of simple cells.[272]

Common descent

Further information: Common descent and Evidence of common descent

All organisms on Earth are descended from a common ancestor or ancestral gene pool.[199][273]

Current species are a stage in the process of evolution, with their

diversity the product of a long series of speciation and extinction

events.[274]

The common descent of organisms was first deduced from four simple

facts about organisms: First, they have geographic distributions that

cannot be explained by local adaptation. Second, the diversity of life

is not a set of completely unique organisms, but organisms that share morphological similarities.

Third, vestigial traits with no clear purpose resemble functional

ancestral traits and finally, that organisms can be classified using

these similarities into a hierarchy of nested groups—similar to a family

tree.[275]

However, modern research has suggested that, due to horizontal gene

transfer, this "tree of life" may be more complicated than a simple

branching tree since some genes have spread independently between

distantly related species.[276][277]

The hominoids are descendants of a common ancestor.

More recently, evidence for common descent has come from the study of biochemical similarities between organisms. For example, all living cells use the same basic set of nucleotides and amino acids.[279] The development of molecular genetics has revealed the record of evolution left in organisms' genomes: dating when species diverged through the molecular clock produced by mutations.[280] For example, these DNA sequence comparisons have revealed that humans and chimpanzees share 98% of their genomes and analysing the few areas where they differ helps shed light on when the common ancestor of these species existed.[281]

Evolution of life

Main articles: Evolutionary history of life and Timeline of evolutionary history of life

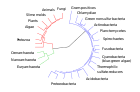

Evolutionary tree showing the divergence of modern species from their common ancestor in the centre.[282] The three domains are coloured, with bacteria blue, archaea green and eukaryotes red.

The history of life was that of the unicellular eukaryotes, prokaryotes and archaea until about 610 million years ago when multicellular organisms began to appear in the oceans in the Ediacaran period.[283][290] The evolution of multicellularity occurred in multiple independent events, in organisms as diverse as sponges, brown algae, cyanobacteria, slime moulds and myxobacteria.[291] In January 2016, scientists reported that, about 800 million years ago, a minor genetic change in a single molecule called GK-PID may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.[292]

Soon after the emergence of these first multicellular organisms, a remarkable amount of biological diversity appeared over approximately 10 million years, in an event called the Cambrian explosion. Here, the majority of types of modern animals appeared in the fossil record, as well as unique lineages that subsequently became extinct.[293] Various triggers for the Cambrian explosion have been proposed, including the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere from photosynthesis.[294]

About 500 million years ago, plants and fungi colonised the land and were soon followed by arthropods and other animals.[295] Insects were particularly successful and even today make up the majority of animal species.[296] Amphibians first appeared around 364 million years ago, followed by early amniotes and birds around 155 million years ago (both from "reptile"-like lineages), mammals around 129 million years ago, homininae around 10 million years ago and modern humans around 250,000 years ago.[297][298][299] However, despite the evolution of these large animals, smaller organisms similar to the types that evolved early in this process continue to be highly successful and dominate the Earth, with the majority of both biomass and species being prokaryotes.[176]

Applications

Concepts and models used in evolutionary biology, such as natural selection, have many applications.[300]Artificial selection is the intentional selection of traits in a population of organisms. This has been used for thousands of years in the domestication of plants and animals.[301] More recently, such selection has become a vital part of genetic engineering, with selectable markers such as antibiotic resistance genes being used to manipulate DNA. Proteins with valuable properties have evolved by repeated rounds of mutation and selection (for example modified enzymes and new antibodies) in a process called directed evolution.[302]

Understanding the changes that have occurred during an organism's evolution can reveal the genes needed to construct parts of the body, genes which may be involved in human genetic disorders.[303] For example, the Mexican tetra is an albino cavefish that lost its eyesight during evolution. Breeding together different populations of this blind fish produced some offspring with functional eyes, since different mutations had occurred in the isolated populations that had evolved in different caves.[304] This helped identify genes required for vision and pigmentation.[305]

Many human diseases are not static phenomena, but capable of evolution. Viruses, bacteria, fungi and cancers evolve to be resistant to host immune defences, as well as pharmaceutical drugs.[306][307][308] These same problems occur in agriculture with pesticide[309] and herbicide[310] resistance. It is possible that we are facing the end of the effective life of most of available antibiotics[311] and predicting the evolution and evolvability[312] of our pathogens and devising strategies to slow or circumvent it is requiring deeper knowledge of the complex forces driving evolution at the molecular level.[313]

In computer science, simulations of evolution using evolutionary algorithms and artificial life started in the 1960s and were extended with simulation of artificial selection.[314] Artificial evolution became a widely recognised optimisation method as a result of the work of Ingo Rechenberg in the 1960s. He used evolution strategies to solve complex engineering problems.[315] Genetic algorithms in particular became popular through the writing of John Henry Holland.[316] Practical applications also include automatic evolution of computer programmes.[317] Evolutionary algorithms are now used to solve multi-dimensional problems more efficiently than software produced by human designers and also to optimise the design of systems.[318]

Social and cultural responses

Further information: Social effects of evolutionary theory, 1860 Oxford evolution debate, Creation–evolution controversy and Objections to evolution

As evolution became widely accepted in the 1870s, caricatures of Charles Darwin with an ape or monkey body symbolised evolution.[319]

While various religions and denominations have reconciled their beliefs with evolution through concepts such as theistic evolution, there are creationists who believe that evolution is contradicted by the creation myths found in their religions and who raise various objections to evolution.[165][321][322] As had been demonstrated by responses to the publication of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1844, the most controversial aspect of evolutionary biology is the implication of human evolution that humans share common ancestry with apes and that the mental and moral faculties of humanity have the same types of natural causes as other inherited traits in animals.[323] In some countries, notably the United States, these tensions between science and religion have fuelled the current creation–evolution controversy, a religious conflict focusing on politics and public education.[324] While other scientific fields such as cosmology[325] and Earth science[326] also conflict with literal interpretations of many religious texts, evolutionary biology experiences significantly more opposition from religious literalists.

The teaching of evolution in American secondary school biology classes was uncommon in most of the first half of the 20th century. The Scopes Trial decision of 1925 caused the subject to become very rare in American secondary biology textbooks for a generation, but it was gradually re-introduced later and became legally protected with the 1968 Epperson v. Arkansas decision. Since then, the competing religious belief of creationism was legally disallowed in secondary school curricula in various decisions in the 1970s and 1980s, but it returned in pseudoscientific form as intelligent design (ID), to be excluded once again in the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District case.[327]

See also

References

- Branch, Glenn (March 2007). "Understanding Creationism after Kitzmiller". BioScience (Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Institute of Biological Sciences) 57 (3): 278–284. doi:10.1641/B570313. ISSN 0006-3568.

Bibliography

- Altenberg, Lee (1995). "Genome growth and the evolution of the genotype-phenotype map". In Banzhaf, Wolfgang; Eeckman, Frank H. Evolution and Biocomputation: Computational Models of Evolution. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 899. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/3-540-59046-3_11. ISBN 3-540-59046-3. ISSN 0302-9743. LCCN 95005970. OCLC 32049812.

- Ayala, Francisco J.; Avise, John C., eds. (2014). Essential Readings in Evolutionary Biology. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1305-1. LCCN 2013027718. OCLC 854285705.

- Birdsell, John A.; Wills, Christopher (2003). "The Evolutionary Origin and Maintenance of Sexual Recombination: A Review of Contemporary Models". In MacIntyre, Ross J.; Clegg, Michael T. Evolutionary Biology. Evolutionary Biology 33. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-3385-0. ISSN 0071-3260. OCLC 751583918.

- Bowler, Peter J. (1989). The Mendelian Revolution: The Emergence of Hereditarian Concepts in Modern Science and Society. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3888-6. LCCN 89030914. OCLC 19322402.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd completely rev. and expanded ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23693-9. LCCN 2002007569. OCLC 49824702.

- Browne, Janet (2003). Charles Darwin: The Power of Place 2. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6837-3. LCCN 94006598. OCLC 52327000.

- Burkhardt, Frederick; Smith, Sydney, eds. (1991). The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. 7: 1858–1859. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38564-4. LCCN 84045347. OCLC 185662993.

- Carroll, Sean B.; Grenier, Jennifer K.; Weatherbee, Scott D. (2005). From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1950-0. LCCN 2003027991. OCLC 53972564.

- Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9. LCCN 2008033973. OCLC 233549529.

- Cracraft, Joel; Bybee, Rodger W., eds. (2005). Evolutionary Science and Society: Educating a New Generation (PDF). Colorado Springs, CO: Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. ISBN 1-929614-23-3. OCLC 64228003. Retrieved 2014-12-06. "Revised Proceedings of the BSCS, AIBS Symposium November 2004, Chicago, IL"

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". In Lewis, C. L. E.; Knell, S. J. The Age of the Earth: from 4004 BC to AD 2002. Geological Society Special Publication 190. London: Geological Society of London. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.2001.190.01.14. ISBN 1-86239-093-2. ISSN 0305-8719. LCCN 2003464816. OCLC 48570033.

- Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 06017473. OCLC 741260650. The book is available from The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Retrieved 2014-11-21.

- Darwin, Charles (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray. LCCN 04002793. OCLC 1102785.

- Darwin, Francis, ed. (1909). The foundations of The origin of species, a sketch written in 1842 (PDF). Cambridge: Printed at the University Press. LCCN 61057537. OCLC 1184581. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- Dawkins, Richard (1990). The Blind Watchmaker. Penguin Science. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-014481-1. OCLC 60143870.

- Dennett, Daniel (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80290-2. LCCN 94049158. OCLC 31867409.

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1968). "On Some Fundamental Concepts of Darwinian Biology". In Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Hecht, Max K.; Steere, William C. Evolutionary Biology. Volume 2 (1st ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8094-8_1. OCLC 24875357.

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1970). Genetics of the Evolutionary Process. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-02837-7. LCCN 72127363. OCLC 97663.

- Eldredge, Niles; Gould, Stephen Jay (1972). "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism". In Schopf, Thomas J. M. Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, Cooper. ISBN 0-87735-325-5. LCCN 72078387. OCLC 572084.

- Eldredge, Niles (1985). Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-49555-0. LCCN 84023632. OCLC 11443805.

- Ewens, Warren J. (2004). Mathematical Population Genetics. Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics. I. Theoretical Introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 0-387-20191-2. LCCN 2003065728. OCLC 53231891.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2004). "The Fruit of the Tree of Life: Insights into Evolution and Ecology". In Cracraft, Joel; Donoghue, Michael J. Assembling the Tree of Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517234-5. LCCN 2003058012. OCLC 61342697. "Proceedings of a symposium held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, 2002."

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005). Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-187-2. LCCN 2004029808. OCLC 57311264.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. LCCN 2001043556. OCLC 47869352.

- Gray, Peter (2007). Psychology (5th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5. LCCN 2006921149. OCLC 76872504.

- Hall, Brian K.; Hallgrímsson, Benedikt (2008). Strickberger's Evolution (4th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-0066-9. LCCN 2007008981. OCLC 85814089.

- Hennig, Willi (1999) [Originally published 1966 (reprinted 1979); translated from the author's unpublished revision of Grundzüge einer Theorie der phylogenetischen Systematik, published in 1950]. Phylogenetic Systematics. Translation by D. Dwight Davis and Rainer Zangerl; foreword by Donn E. Rosen, Gareth Nelson, and Colin Patterson (Reissue ed.). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06814-9. LCCN 78031969. OCLC 722701473.

- Holland, John H. (1975). Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08460-7. LCCN 74078988. OCLC 1531617.

- Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J. (2005). Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Illustrations by Anna Zeligowski. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-10107-6. LCCN 2004058193. OCLC 61896061.

- Kampourakis, Kostas (2014). Understanding Evolution. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03491-4. LCCN 2013034917. OCLC 855585457.

- Kirk, Geoffrey; Raven, John; Schofield, Malcolm (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts (2nd ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27455-9. LCCN 82023505. OCLC 9081712.

- Koza, John R. (1992). Genetic Programming: On the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection. Complex Adaptive Systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-11170-5. LCCN 92025785. OCLC 26263956.

- Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1809). Philosophie Zoologique. Paris: Dentu et L'Auteur. OCLC 2210044. Philosophie zoologique (1809) on Internet Archive. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- Lane, David H. (1996). The Phenomenon of Teilhard: Prophet for a New Age (1st ed.). Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-498-0. LCCN 96008777. OCLC 34710780.

- Magner, Lois N. (2002). A History of the Life Sciences (3rd rev. and expanded ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-0824-5. LCCN 2002031313. OCLC 50410202.

- Mason, Stephen F. (1962). A History of the Sciences. Collier Books. Science Library, CS9 (New rev. ed.). New York: Collier Books. LCCN 62003378. OCLC 568032626.

- Maynard Smith, John (1978). The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29302-2. LCCN 77085689. OCLC 3413793.

- Maynard Smith, John (1998). "The Units of Selection". In Bock, Gregory R.; Goode, Jamie A. The Limits of Reductionism in Biology. Novartis Foundation Symposia 213. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470515488.ch15. ISBN 0-471-97770-5. ISSN 1935-4657. LCCN 98002779. OCLC 38311600. PMID 9653725. "Papers from the Symposium on the Limits of Reductionism in Biology, held at the Novartis Foundation, London, May 13–15, 1997."

- Mayr, Ernst (1942). Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist. Columbia Biological Series 13. New York: Columbia University Press. LCCN 43001098. OCLC 766053.

- Mayr, Ernst (1982). The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. Translation of John Ray by E. Silk. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-36445-7. LCCN 81013204. OCLC 7875904.

- Mayr, Ernst (2002) [Originally published 2001; New York: Basic Books]. What Evolution Is. Science Masters. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-60741-3. LCCN 2001036562. OCLC 248107061.

- McKinney, Michael L. (1997). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". In Kunin, William E.; Gaston, Kevin J. The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences (1st ed.). London; New York: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-412-63380-9. LCCN 96071014. OCLC 36442106.

- Miller, G. Tyler; Spoolman, Scott E. (2012). Environmental Science (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-1-111-98893-7. LCCN 2011934330. OCLC 741539226. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

- Moore, Randy; Decker, Mark; Cotner, Sehoya (2010). Chronology of the Evolution-Creationism Controversy. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36287-3. LCCN 2009039784. OCLC 422757410.

- Nardon, Paul; Grenier, Anne-Marie (1991). "Serial Endosymbiosis Theory and Weevil Evolution: The Role of Symbiosis". In Margulis, Lynn; Fester, René. Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13269-9. LCCN 90020439. OCLC 22597587. "Based on a conference held in Bellagio, Italy, June 25–30, 1989"

- National Academy of Sciences; Institute of Medicine (2008). Science, Evolution, and Creationism. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10586-6. LCCN 2007015904. OCLC 123539346. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- Odum, Eugene P. (1971). Fundamentals of Ecology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-6941-7. LCCN 76081826. OCLC 154846.

- Okasha, Samir (2006). Evolution and the Levels of Selection. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926797-9. LCCN 2006039679. OCLC 70985413.

- Panno, Joseph (2005). The Cell: Evolution of the First Organism. Facts on File science library. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4946-7. LCCN 2003025841. OCLC 53901436.

- Piatigorsky, Joram; Kantorow, Marc; Gopal-Srivastava, Rashmi; Tomarev, Stanislav I. (1994). "Recruitment of enzymes and stress proteins as lens crystallins". In Jansson, Bengt; Jörnvall, Hans; Rydberg, Ulf; et al. Toward a Molecular Basis of Alcohol Use and Abuse. Experientia 71. Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-7330-7_24. ISBN 3-7643-2940-8. ISSN 1023-294X. LCCN 94010167. OCLC 30030941. PMID 8032155.

- Provine, William B. (1971). The Origins of Theoretical Population Genetics. Chicago History of Science and Medicine (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-68464-4. LCCN 2001027561. OCLC 46660910.

- Provine, William B. (1988). "Progress in Evolution and Meaning in Life". In Nitecki, Matthew H. Evolutionary Progress. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-58693-6. LCCN 88020835. OCLC 18380658. "This book is the result of the Spring Systematics Symposium held in May, 1987, at the Field Museum in Chicago"

- Quammen, David (2006). The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution. Great Discoveries (1st ed.). New York: Atlas Books/W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05981-6. LCCN 2006009864. OCLC 65400177.

- Raven, Peter H.; Johnson, George B. (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-112261-3. LCCN 2001030052. OCLC 45806501.

- Ray, John (1686). Historia Plantarum [History of Plants] I. Londini: Typis Mariæ Clark. LCCN agr11000774. OCLC 2126030.

- Rechenberg, Ingo (1973). Evolutionsstrategie; Optimierung technischer Systeme nach Prinzipien der biologischen Evolution (PhD thesis). Problemata (in German) 15. Afterword by Manfred Eigen. Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt: Frommann-Holzboog. ISBN 3-7728-0373-3. LCCN 74320689. OCLC 9020616.

- Ridley, Matt (1993). The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-84357-1. OCLC 636657988.

- Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, Stephen C. (1999). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07606-1. LCCN 98034087. OCLC 47011675. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

- Stevens, Anthony (1982). Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-0980-1. LCCN 84672250. OCLC 10458367.

- West-Eberhard, Mary Jane (2003). Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512235-6. LCCN 2001055164. OCLC 48398911.

- Wiley, E. O.; Lieberman, Bruce S. (2011). Phylogenetics: Theory and Practice of Phylogenetic Systematics (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781118017883. ISBN 978-0-470-90596-8. LCCN 2010044283. OCLC 741259265.

- Wright, Sewall (1984). Genetic and Biometric Foundations. Evolution and the Genetics of Populations 1. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91038-5. LCCN 67025533. OCLC 246124737.

Further reading

Further information: Bibliography of biology

| Library resources about Evolution |

Introductory reading

- Barrett, Paul H.; Weinshank, Donald J.; Gottleber, Timothy T., eds. (1981). A Concordance to Darwin's Origin of Species, First Edition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1319-2. LCCN 80066893. OCLC 610057960.

- Carroll, Sean B. (2005). Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom. illustrations by Jamie W. Carroll, Josh P. Klaiss, Leanne M. Olds (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06016-0. LCCN 2004029388. OCLC 57316841.

- Charlesworth, Brian; Charlesworth, Deborah (2003). Evolution: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280251-8. LCCN 2003272247. OCLC 51668497.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1989). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-02705-8. LCCN 88037469. OCLC 18983518.

- Jones, Steve (1999). Almost Like a Whale: The Origin of Species Updated. London; New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-40985-0. LCCN 2002391059. OCLC 41420544.

- —— (2000). Darwin's Ghost: The Origin of Species Updated (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50103-7. LCCN 99053246. OCLC 42690131. American version.

- Mader, Sylvia S. (2007). Biology. Significant contributions by Murray P. Pendarvis (9th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-246463-4. LCCN 2005027781. OCLC 61748307.

- Maynard Smith, John (1993). The Theory of Evolution (Canto ed.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45128-0. LCCN 93020358. OCLC 27676642.

- Pallen, Mark J. (2009). The Rough Guide to Evolution. Rough Guides Reference Guides. London; New York: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-946-5. LCCN 2009288090. OCLC 233547316.

- Barton, Nicholas H.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Eisen, Jonathan A.; et al. (2007). Evolution. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-684-9. LCCN 2007010767. OCLC 86090399.

- Coyne, Jerry A.; Orr, H. Allen (2004). Speciation. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-089-2. LCCN 2004009505. OCLC 55078441.

- Bergstrom, Carl T.; Dugatkin, Lee Alan (2012). Evolution (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-91341-5. LCCN 2011036572. OCLC 729341924.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. LCCN 2001043556. OCLC 47869352.

- Hall, Brian K.; Olson, Wendy, eds. (2003). Keywords and Concepts in Evolutionary Developmental Biology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00904-5. LCCN 2002192201. OCLC 50761342.

- Maynard Smith, John; Szathmáry, Eörs (1995). The Major Transitions in Evolution. Oxford; New York: W.H. Freeman Spektrum. ISBN 0-7167-4525-9. LCCN 94026965. OCLC 30894392.

- Mayr, Ernst (2001). What Evolution Is. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04426-3. LCCN 2001036562. OCLC 47443814.

- Minelli, Alessandro (2009). Forms of Becoming: The Evolutionary Biology of Development. Translation by Mark Epstein. Princeton, NJ; Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13568-7. LCCN 2008028825. OCLC 233030259.

External links

Listen to this article (info/dl)

This audio file was created from a revision of the "Evolution" article dated 2005-04-18, and does not reflect subsequent edits to the article. (Audio help)

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| News stories from Wikinews | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- General information

- Evolution on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)

- "Evolution". New Scientist. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Evolution Resources from the National Academies". Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Understanding Evolution: your one-stop resource for information on evolution". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- "Evolution of Evolution – 150 Years of Darwin's 'On the Origin of Species'". Arlington County, VA: National Science Foundation. Retrieved 2011-05-30.

- Experiments concerning the process of biological evolution

- Lenski, Richard E. "Experimental Evolution". Michigan State University. Retrieved 2013-07-31.